In 1842, the U.S. Supreme Court delivered a landmark ruling that reverberates through American jurisprudence even today. The case, Prigg v. Pennsylvania, centered around Edward Prigg, a white man who had forcibly seized a Black family, including Margaret Morgan and her children, compelling them into slavery. This incident unfolded against the backdrop of a nation grappling with its own contentious relationship with the institution of slavery, particularly along the Mason-Dixon line.

- Prigg v. Pennsylvania still cited today

- Slavery precedents influence American law

- Educational reforms target racial history topics

- Legal system rooted in slavery concepts

- Acknowledging slavery's history is crucial

- New citation guidelines for enslaved individuals

The court’s ruling was stark. It declared Pennsylvania’s anti-slavery law an unconstitutional infringement on the federal Fugitive Slave Act. The justices articulated a powerful message: the ownership of enslaved individuals was a fundamental right, a notion deeply embedded within the U.S. Constitution itself. “The citizens of the slaveholding states,” the court noted, “held complete right and title of ownership in their slaves as property, in every state in the Union.” The weight of this decision underscored not just the legal standing of slavery, but also revealed how inseparably intertwined it was with the very fabric of the nation’s founding.

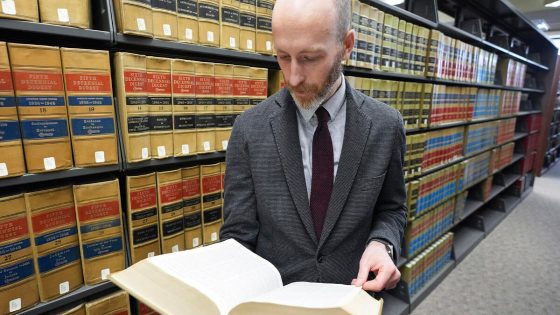

Today, over 160 years later, Prigg continues to be cited in legal decisions across the country—274 times, according to the Citing Slavery Project at Michigan State University. This ongoing reference highlights the enduring legacy of slavery in American law, much to the dismay of advocates who argue that it perpetuates the systemic inequalities rooted in our history. As Justin Simard, the project’s director and a law professor, pointed out, “People are invested in trying to pretend that our history of slavery didn’t happen and that its effects are not still with us.”

The implications of these precedents stretch far beyond their historical context, influencing current legal cases and decisions. “These slavery precedents show us that this is not just a historic stain that the 13th Amendment cleaned up,” said Leonard Mungo, a civil rights attorney. He emphasized the pervasive nature of these citations, which affect not only marginalized communities but also individuals from various backgrounds, as illustrated in a 1989 Supreme Court ruling affecting a white football coach’s discrimination claim.

Mungo’s insights reflect a troubling reality: the principles established under slavery continue to shape judgments in cases involving civil rights, property law, and employment discrimination. This alarming trend forces us to confront uncomfortable truths about the foundations of American law—a system that often fails to adequately protect the rights of individuals when influenced by outdated precedents grounded in the ideologies of slavery.

In a striking example, dissenting justices in a 2016 Iowa Supreme Court case utilized historical references to the Fugitive Slave Act to argue for providing arrestees the right to private attorney consultations. They pointed out that if enslaved individuals could assert a right to counsel, then surely so should modern defendants facing criminal charges. Unfortunately, the dissent was overruled, underscoring the continuing tension around these issues.

Simard’s research, which originally began as a dissertation, has uncovered more than 12,000 slavery-related rulings, revealing a widespread and troubling reliance on these cases within the legal framework. “This was just a basic feature of the legal system,” he remarked, astonished by its reach and implications.

Simard and his team have recently taken proactive steps to ensure that legal documents more accurately reflect the historical context of these cases. They successfully lobbied to amend guidelines for legal citations, pushing for terms like “enslaved party” or “enslaved person at issue” to be utilized. His assertion that “the best approach…is to be thoughtful when they find these cases and cite these cases” reflects a growing awareness among legal professionals about the need to confront this history.

As we look towards the future, experts agree that while completely removing these cases from the legal lexicon may be impractical, a shift in how they are perceived and cited can redefine their influence. “If lawyers stop relying on these cases, they lose their power,” noted civil rights advocates, emphasizing the vital importance of recognizing the historical contexts surrounding these legal precedents.

Ultimately, acknowledging the legacy of slavery within the legal system compels us to confront not just the past, but also the present. As Michigan Appeals Court Judge Adrienne Young affirmed, “The real harm is in failing to acknowledge the horrific history.” In grappling with this history, society might begin to forge a more equitable future as we seek justice for all.

![[EN DIRECTE] Decretada l’emergència per inundacions a bona part del País Valencià - VilaWeb](https://news.faharas.net/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/Emergency-Declared-as-Devastating-Floods-Ravage-Much-of-Valencia-Region-230x129.jpg)