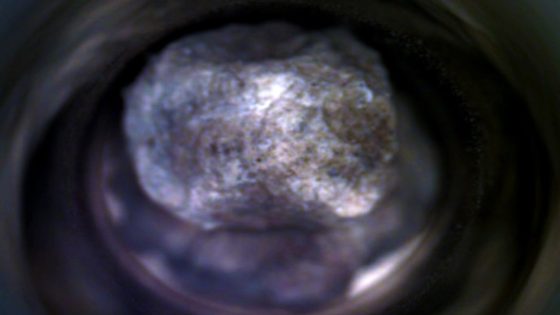

In a surprising discovery, a man found ancient fossilized vomit dating back 66 million years. This unusual find was made along the stunning cliffs of Stevns Klint in Denmark, a site renowned for its rich fossil history. What secrets does this ancient regurgitate hold about life in the Cretaceous era?

- Fossilized vomit discovered in Denmark

- Dates back 66 million years

- Contains sea lilies consumed by fish

- Found at UNESCO-listed Stevns Klint

- Provides insights into ancient food chains

- Exhibition available at Geomuseum Faxe

Discovering Ancient Fossils: What This Find Means for Science

Could fossilized vomit provide clues about ancient ecosystems? This remarkable discovery in Denmark sheds light on the diets of prehistoric creatures. The fossilized remains, known as coprolites, offer a window into the past, revealing the types of food consumed by marine predators.

Fossilized Vomit: A Window into the Cretaceous Era

The fossilized vomit, discovered by Peter Bennicke, contains remnants of sea lilies, which were likely consumed by a fish predator. This find is not just a curiosity; it provides essential information about the food chains of the Cretaceous seas. Here are some key points:

- The vomit dates back 66 million years, offering insights into ancient diets.

- It was found at Stevns Klint, a UNESCO World Heritage site known for fossils.

- Experts identified at least two species of sea lilies in the fossil.

- This discovery enhances our understanding of predator-prey relationships in ancient ecosystems.

Why Fossilized Vomit Matters in Paleontology

Fossilized vomit may seem unappealing, but it holds great importance in paleontology. By studying these remnants, scientists can learn about the diets of ancient animals and their ecological roles. This knowledge helps reconstruct ancient environments and understand how ecosystems have evolved over millions of years. The information gained from such fossils can also inform current ecological studies.

What This Discovery Reveals About Ancient Marine Life

This fossilized vomit reveals that ancient fish had varied diets, including sea lilies, which are relatives of modern sea stars. These findings challenge our understanding of what constituted a predator’s meal in the Cretaceous seas. The relationship between these ancient fish and their food sources reflects the complex dynamics of marine life millions of years ago.

In conclusion, the discovery of fossilized vomit in Denmark not only highlights the fascinating history of our planet but also emphasizes the importance of every find, no matter how unusual. Such discoveries continue to enrich our understanding of the ancient world.