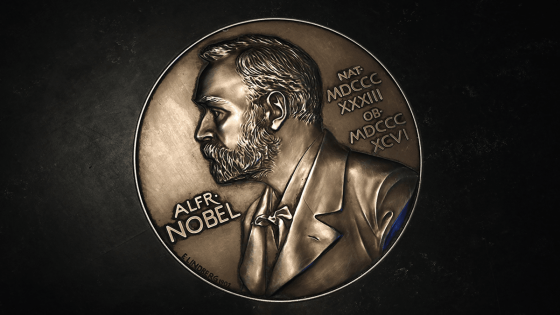

Imposter syndrome is a common experience, even among the most celebrated scientists. Albert Einstein, a Nobel Prize winner, once expressed discomfort with the accolades he received, feeling like an “involuntary swindler.” This sentiment resonates with many who achieve great success, as seen in various Nobel laureates who later embraced pseudoscientific beliefs.

- Einstein experienced imposter syndrome despite achievements.

- "Nobel disease" describes unscientific beliefs post-award.

- Some Nobel winners pursued paranormal interests.

- Harmful pseudoscientific beliefs emerged among laureates.

- Media pressure influences Nobel winners' opinions.

- Cognitive errors may lead to flawed thinking.

In a fascinating exploration of this phenomenon, researchers have coined the term “Nobel disease” to describe the often bizarre beliefs that some Nobel Prize winners adopt post-award. For instance, Kary Mullis, who shared the 1993 Nobel Prize in Chemistry, famously claimed to have encountered a glowing raccoon on a motorcycle. Such anecdotes raise questions about the pressures and expectations placed on these esteemed individuals, especially since they may feel compelled to comment on topics outside their expertise.

This raises an important question: why do some of the brightest minds stray into pseudoscience? External pressures from media and public expectations can lead to cognitive biases, resulting in a detachment from scientific rigor. Consider these points:

- High expectations can distort self-perception.

- Media attention may encourage exploration beyond expertise.

- Cognitive biases can lead to critical thinking errors.

- Famous scientists are often viewed as experts in all fields.

As we move forward, it’s vital to encourage Nobel Prize winners and other scientists to remain grounded in their fields. This will not only enhance scientific integrity but also inspire future generations to pursue knowledge with clarity and focus.